In 2018, the question of union dues and membership made national news during the Janus v AFSCME Supreme Court case. The Court ruled (5-4) that members of public sector unions could not be compelled to pay dues, agreeing with the argument that mandatory fees violated “free speech”. The case was funded in part by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation - an explicitly anti-union policy group.

So what exactly is “right-to-work” and why does it matter to the labor movement?

Union security contract language

Almost all unions fight for a contractual union security clause. In workplaces with “union security,” everyone covered by the contract must join the union and pay full dues or otherwise elect “fee payer” status. Membership is totally voluntary when a contract does not include a union security clause. This can be because the company is based in a right-to-work state or in cases where unions do not have the leverage to win it in negotiations. Right-to-work laws currently prohibit union security language in but even in states without right-to-work laws, unions still have to win the language in negotiations.

Union security requires workers to pay dues as a condition of their employment. This is often cited as an anti-union scare tactic (as in: “the union just wants your money or they’ll get you fired”). The reality is that the union is required to negotiate on behalf of all workers in the bargaining unit - even those that aren’t paying dues. If someone isn’t paying their fair share, they are actively hurting the ability of the union to win and enforce good contracts for everyone.

Employers almost always use dues to try to dissuade people from organizing a union, because they realize that if you form a union, you will likely negotiate a raise to cover your dues and more. If you’re unsure about their motivations, how often are those same employers taking a stand on issues that benefit workers, like rent control or accessible transportation? (hint: they’re not)

Right-to-work laws

Union security is not enforceable in the 27 states with right-to-work legislation; in these states, no one can be required to pay dues or join the union. This is based on where the worker lives, not where the company is based.

Every single benefit and protection found in the union contract (from raises to severance to paid family leave) applies to everyone in the unit, whether or not they pay dues. This is the reason that many unions have fought hard for union security and against right-to-work laws; when people don’t pay their fair share, it weakens the union. The term “right-to-work” intentionally frames unions as the opposition to employment. In reality, it’s a “right-to-work-for-less” law that limits the freedom of union workers to negotiate for a union shop.

Fee payer status and paying a fair share

In union shops, there is a third option for people who do not live in right-to-work states but who object to union membership: fee payer status. Fee payers pay agency fees - or a “fair share” - which is a slightly smaller percentage than full dues and is determined on an annual basis at each union. Agency fee payments cover the costs of representation only and cannot be used for organizing or political work. Fee payers meet their obligation under union security but typically aren’t able to participate in certain union activities, including elections that determine the leadership of the union or voting on contracts before they go into effect.

The cost of not joining a union

We can’t talk about dues as a dollar amount in isolation from the overall value of union employment. Dues are set by each individual union and are usually around 1-2% of union-covered earnings; earning a union wage more than covers the cost of dues. While the exact differences vary slightly depending on the industry, the trend is clear year after year - union workers far outearn non-union workers.

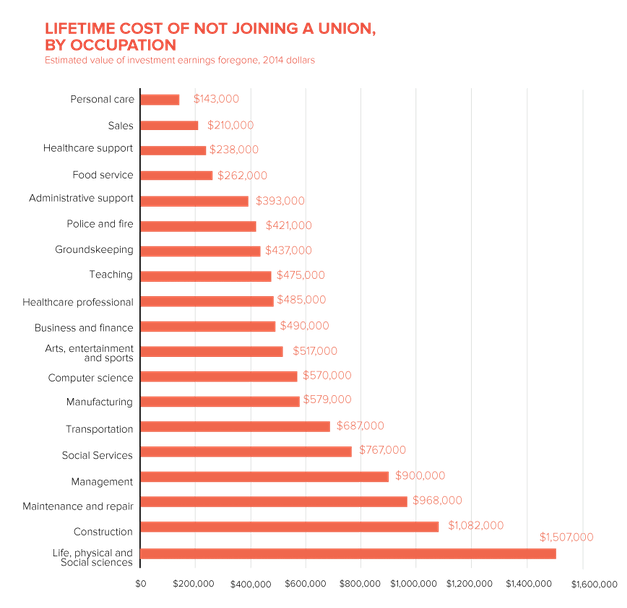

In 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that “union members had median usual weekly earnings of $1,144 in 2020, while those who were not union members had median weekly earnings of $958.” A similar study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) reported that unionized workers earn 11.2% more in wages than comparable workers. These differences add up! A report from The Century Foundation (TCF) calculated that a $400 difference in weekly pay between comparable union and non-union workers compounds (on average) to over half a million dollars in lost earnings in a workers’ lifetime (see chart below). They concluded that joining a union is one of the most significant investments a worker can make.

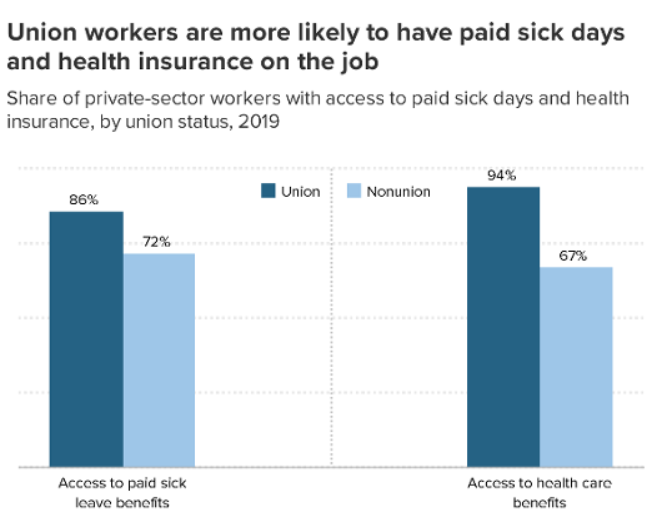

Collective bargaining raises overall wages and can set minimum pay rates and annual raises, which reduces gender and race disparities in pay. Additional union benefits - like health care, paid leave, and retirement benefits - also impact take-home pay and overall worker security. Not only that, nonunion workers still benefit from unionization because employers have to raise benefits and wages to compete for the same workforce.

Worker power requires resources

The basic assurance of financial resources allows unions to continue organizing to build and maintain collective power. Union members and workers across the country are taking on major corporations like Amazon, Spotify, and Google; new campaigns are made possible because of current union members' dues. Organizing requires resources!

Membership and paying dues is a tangible expression of solidarity - it is the actualization of the belief that we are better off together than we are alone. This is not just an ideological distinction; right-to-work is a political strategy designed specifically to weaken unions and divide workers against each other. It has explicitly racist origins and was championed by segregationists who opposed the employment of Black workers.

Dues are an investment in both the short and long-term future of workers, the more people who are organized and fighting for the rights the better off we all are.